🌳Is There a Perfect Category?

A few flomoers may ask: How should I categorize all my MEMOs? How should I use tags? But these are not the real question. The real question is how we should organize information.

Using folders is a traditional mindset

From the Library of Alexandria to Wikipedia, there are two important topics in knowledge management, which are, store and organize.

When we organize the knowledge, we have many choices. But most of the note-taking tools follow the organizing rule of folders, which means a knowledge unit is saved to a certain folder in a specific route. When a project is related to a lot of other things, you can use tags. But each file is usually saved in one hierarchy. If a user wants to use the file, he or she must remember the folder route or use the search to locate it.

But when you collect information, you will quickly find that a file can be connected with a lot of questions.

If you collect information in a folder, you may find that it’s hard to connect them all together. The information without contexts may be forgotten in some solitary corner.

More importantly, each article has knowledge chunks, which connect with a few others in your thinking pattern. This will put you into a dilemma as well. If an article is connected with three areas you are currently working on, then should you put copies of it into every area folder? If you do, then each time when you modify this article, your efforts need to triple.

A structure grows itself

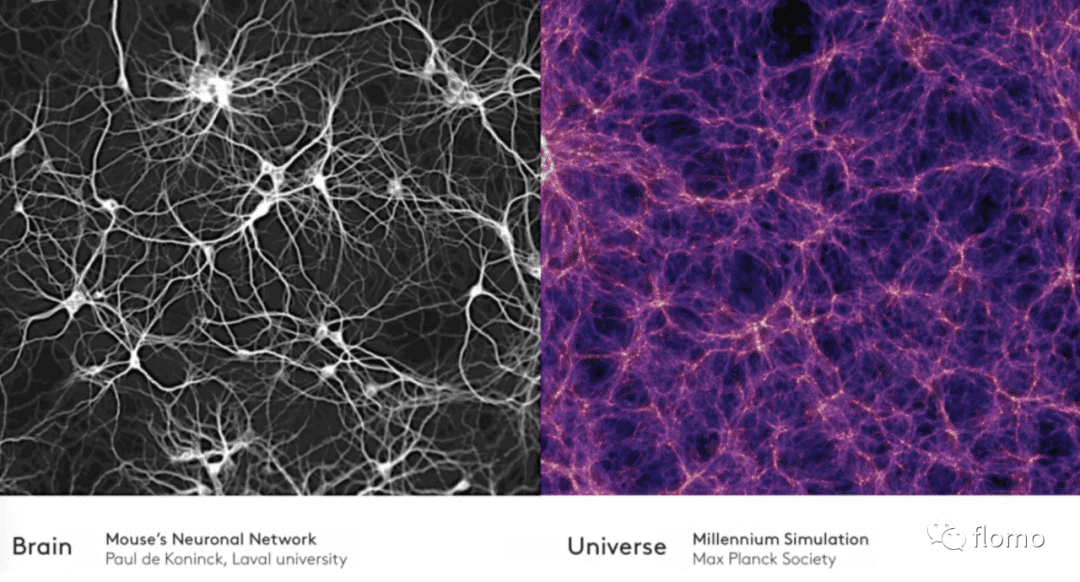

On the left is our neuron cells, while on the right is the stimulated universe we already knew. It seems that there is a rare “well-structured” category at both macro and micro levels in nature. The picture looks like a network built by nodes and connections. The important nodes are expanding. Many nodes will build more connections based on your accumulation.

Luhman had realized this fact very early. He repeatedly emphasized that creating a category is a top-down process. You start by building the structure and then categorizing files. But our brains don’t work in the category. When knowledge adds up, the network of things we knew will grow naturally. It’s not a scaffold but a plant.

For example, when I learned knowledge about trading platforms, much of it will not unfold as in the following picture. Instead, much knowledge will come to me randomly.

The first knowledge chunk is “value unit” which comes from an article about the methodology of Booking. I didn’t pay much attention to it after taking notes.

The second knowledge chunk is a book named Code Version 2.0. It has no connection with the trading platform (at least I thought it didn’t).

The third knowledge chunk is the “core elements of trading platforms”. After learning it, I realized that the first knowledge chunk could be put in this category. While the second chunk is at the same level as the third chunk.

Based on the third chunk, I learned the fourth chunk in the relevant book Platform Revolution.

Based on the second chunk, I dug out the fifth chunk in Code Version 2.0.

Though this mind map looks organized, the learning process is hardly similar. It can’t be possible to learn in this way. This structure grew itself.

Laura, one of flomo users, had ever told a story about “the structure of knowledge grows itself”:

There is a reason why we prefer the “systematic”. It brings us a sense of safety and a sense of grasping the knowledge. When we were at school, our teachers would teach us to “systematically” learn something. In the library or Wikipedia, the documents are formed in a systematic way. So when we manage our own knowledge, we would like to use a similar organized method to categorize it. But such categories are built based on the knowledge that already exists in an area. For example, if a textbook author is a master in a certain area, he may write a textbook based on a framework because his knowledge of the area gives him the ability to build a system. As a learner, the way you manage your knowledge is naturally different from the way a textbook is compiled by a master. You may collect a few chunks here, and some chunks there. Later, you may form the network of this area. I remember when I was a kid, my teacher called the excerpt notebook “collecting honey”. If we are learning knowledge from different areas, we need to actively connect the dots. These are something that we don't expect when we try to build a “system”.

Categories are like buildings. Once built, it may encounter the problem of re-building. While absorbing knowledge is more like the process of neural circuits being enhanced or decreased. After continuous collection, the structure will grow itself. So it is meaningless and impossible to build a precise category from scratch unless you stop growing.

Is organizing a goal or a path?

A good system never costs you lots of effort to organize. If you need to organize a system regularly, then it is contrary to the goal of a system. Because except wasting time, organizing notes could provide nothing else.

A better method is allowing your system to grow naturally with the changes in your knowledge. More importantly, you should use questions to motivate you to explore areas. Through deliberate practices, you then earn some compound interests in a certain area.

Organizing is a path rather than a goal. The real goal is to find our progress in a certain area.

Last updated