🪧Why Should We Use Cards for Note-taking

What is Zettelkasten

Zettelkasten, perhaps some of you are very familiar with it. It is a German word equal to slip-box in English.

Essentially, Zettelkasten is a process rather than a tip. It is a method of stashing and organizing knowledge, expanding our memory, and generating new ideas. Or we can say, it encourages you to collect all the knowledge you need and process it in a standardized way. After connecting the dots among notes, you may know how to use them.

As a tool, Zettelkasten is a box (or a set of boxes) for index cards or memos. There is a piece of information, an index, and a source of information on each memo. Normally, these memos should be as short as a few words or sentences. The cards should not be large, so they can be simple and neat. Pictures and other forms also work.

But the point is you should write down in your own words rather than copy information. When you read new information from other resources, you should process it in your own way. Don’t worry that your understanding is not precise because you can put all the metadata including the source on the cards.

The core idea here is to keep permanent notes for your future. Write down immediately; write down in a clear and simple way as if you are going to show somebody else. Regard the process of writing a wiki. You may lack skills but are full of resources and indexes.

Of course, the whole process of Zettelkasten requires practice and patience. When the cards are accumulated, you will have an incredibly large knowledge base.

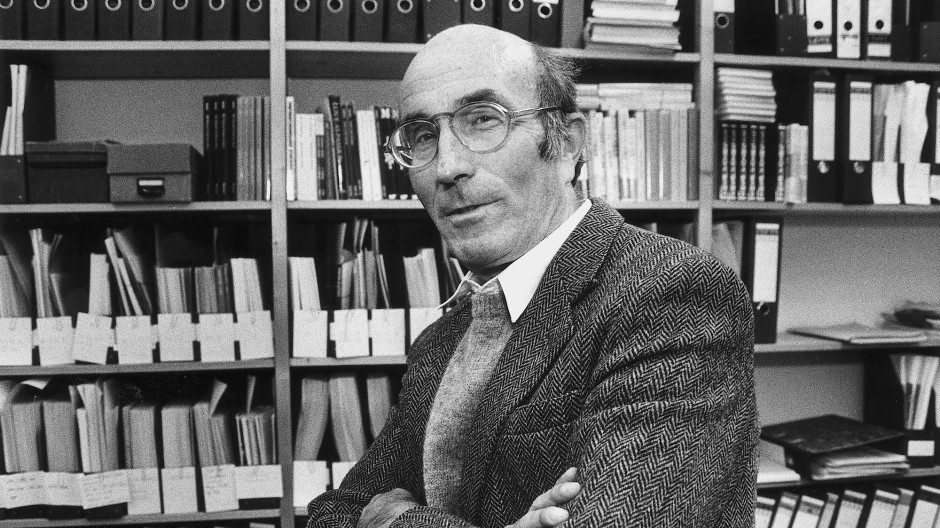

Luhmann used this method to accumulate 90,000 knowledge cards and wrote 60 books and numerous other publications in his lifetime. In 1968, when Luhmann published his thesis at the new university, he received a questionnaire about the content of his research. His answer was this: ”Project: Sociological Theory. Duration: 30 years. Cost: Zero .“[1]

The principles behind the cards

“Chunk” is a technical word in psychology, which means the knowledge unit you are very familiar with and can search in your memory index. Since it exists in the index, the chunks are anything you can think about in the professional area.

For example, each English speaker has stored more than 100,000 chunks, which are called “words”. When we read some words in a passage, we search for their meanings in our memory.

The idea of chunks comes from a dissertation named What We Know About Learning by Herbert A. Simon.

While in Nicolas Luhmann’s opinion, the cards advocated in his Zettelkasten are similar to the chunks.

So, while learning, we don’t grasp the whole knowledge system once and for all. Instead, we accumulate knowledge points or chunks or cards, whatever, gradually.

The difference between a professional and a nonprofessional is the chunks they have. A professional may have 50,000 to 100,000 chunks of knowledge.

Although a card is simple, it can build a complex structure through cards by cards. All the complex structure comes from the accumulation of the smallest unit. Think about the ants, the bees, the cities. So does the palace of knowledge.

The structure of a card

Let’s see the structure of Luhmann’s cards.

Unique identifier gives your cards a specific address. In flomo, the unique identifier is the time stamp.

Body is where you write down the parts of knowledge. In flomo, it is the body of MEMO.

References allow you to write down the source of knowledge. If thoughts belong to yourself, then you can leave out the references. In flomo, annotating a MEMO is inspired by references.

The body of a card is vital. That’s why flomo doesn’t support excerpts or import API. Because the heart of the Zettelkasten is using your own words to record everything rather than copy and paste. Copy-and-paste only makes you a carrier of knowledge rather than a rebuilder.

Compared with recording a lot of content at once, a few atomic cards may help you more. That’s why I insist that the input field should be as simple as possible.

What to record on a card?

While using the Zettelkasten, adding MEMOs without thinking will reduce the quality. Besides the quality, the quantity is also needed to witness a quality leap. There are three types of notes:

Fleeting notes are the reminder of information. You just jot down a few words, and later they might be dumped or be archived to be permanent notes.

Project notes only relate to a specific project.

Permanent notes will never be dumped. They have the necessary information, and they exist in a permanent and understandable way. Permanent notes are the result of processing the above two types of notes.

Suggestions on writing cards

Not all of us will become writers or publish dissertations. But all of us need to record and think.

The value of writing MEMOs (cards) rather than articles is to facilitate our thinking. No one is creating from scratch. They always need accumulation.

So here I would like to give you some suggestions on writing MEMOs (credit to Yang Zhiping):

While writing a card, do not think of posting it to social media. Posting cards will increase your cognitive load. All you need to do is to write down instead of increasing your social assets.

You should write down “counter common sense”, “names”, and “terms” on cards. “Counter common sense” is used to expand your cognitive boundaries. “Names” is used to memorize the creator of knowledge. “Terms” are used to memorize the source of knowledge.

It is recommended to write three cards every day at least, and nine cards the best. But don’t write too many cards because it is hard to remember them all the next day.

More importantly, making progress through small actions and a long period can last longer than impulse efforts.

The benefits

Many times, when we are faced with a blank editor with a flashing cursor, we try to dig out our minds with something completely new, and after a few minutes, we realize that it is in vain. As time passes we will tell ourselves, "It seems that we don’t have that much creativity.”

But the truth is nobody is creating from scratch.

Anything new must come from previous experiences, research, or insights.

As knowledge workers, we shall know the rule is that researches and accumulations always come first. In other words, we should do some research before writing down anything. Then we will have weeks even months of accumulated materials for reference.

That’s why we created flomo.

Because most of the other note-taking tools are like a blank canvas encouraging you to paint on it. But flomo would like to be your knowledge database that integrates all your thoughts, observations, research, and ideas.

Many of us don’t have such a habit of accumulating ideas. So when we are going to write down something, it’s hard to find the resources. That’s the reason why we sometimes fail in writing. Since they haven’t been taking notes from the start, they either have to start with something completely new (which is risky) or retrace their steps (which is boring). [2] You’ll see the changes brought by a habit when the problem of not having enough to write about is replaced by the problem of having far too much to write about.

Reference:

[1]https://blog.karthisoftek.com/a?ID=01700-041199e4-093b-4a51-8a54-dc32be643092

Last updated